Impact of the Garment Industry on Rural Livelihoods: Lessons from Prey Veng Garment Workers and Rural Households, October 2005

Cambodia’s transition from a centrally planned to a market economy in the early 1990s actively encouraged foreign direct investment and the privatization of industries. This created the business climate in which the garment industry was able to find a niche and flourish. The installation of the democratically elected Royal Government of Cambodia in 1993 likewise allowed the country to reestablish trade relationships with western governments. Garment exports grew rapidly after 1996 when favorable trade agreements were signed, first with the European Union (EU) and then with the United States (US). In 2004, the industry generated US$1.95 billion in sales from 206 factories employing about 245,000 workers.

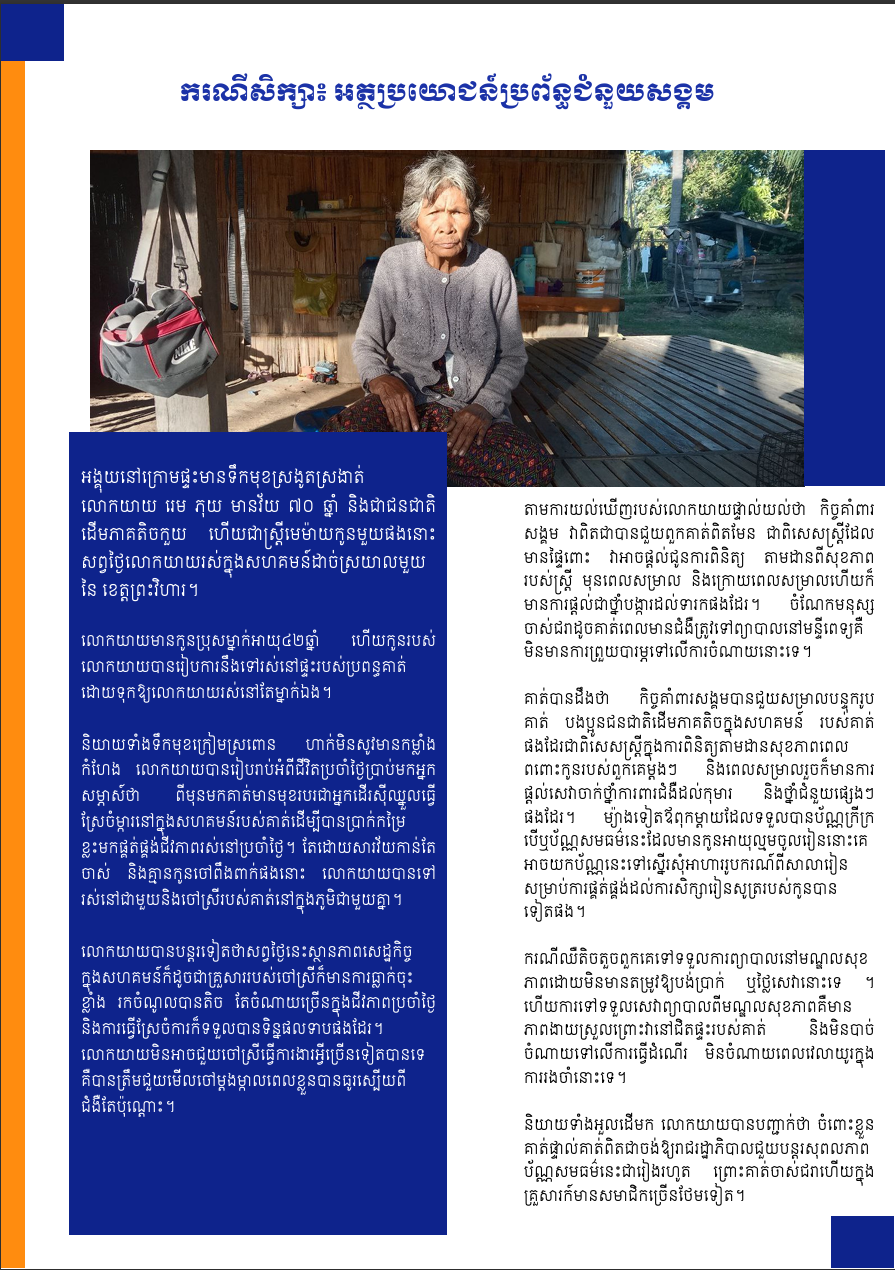

With most factories established in Phnom Penh, rural villagers migrated to the city to take advantage of the job opportunities available in the garment sector. Most of these migrants were young women who came from surrounding provinces. The prerequisite demand for young female labor occasioned a shift in traditional rural practices, as previously men from rural households traveled to Phnom Penh for seasonal work while women, especially unmarried girls, stayed at home. Certainly, the promise of employment in US dollar wages was a strong pull factor attracting female workers to Phnom Penh. But push factors were likewise at work. Due to successive floods and droughts, and high production costs, returns to rice farming were decreasing. At the same time there were few opportunities in rural off-farm work. Migrant work to Phnom Penh, and increasingly to Thailand and Viet Nam, had become a common livelihood strategy of the rural poor.

Cambodia’s garment trade agreement with the United States was linked to improved labor standards, and workers did benefit from this arrangement. Nevertheless, women had to work long hours to ensure that they had sufficient wages to remit part of what they earned back to their families in the province. This often left them tired and weak. Meanwhile, many workers endured crowded living conditions with inadequate facilities. Still they endured the hardships of the work and came to enjoy the small delights of the city, demonstrating a strong desire and commitment to help their families in the rural areas. The prevailing situation though was about to change dramatically at the end of 2004. The future work of the garment workers, indeed the very viability of Cambodia’s garment industry, was threatened at year-end 2004 by the expiration of favorable trade agreements and heightened competition in the global garment market. This sparked much discussion on the future prospects of the garment industry and its consequences for the Cambodian economy.